July 15, 2020 video: Slow Boat to Justice–Prosecuting Foreign Drug Counterfeiters

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has a pending rule that, if finalized, would allow states to import prescription drugs from Canada. Importing medicine from Canada, however, is more dangerous than it looks because it is so difficult to prosecute fake or substandard drug sellers. Legislators and their consultants make it sound as if holding a foreign vendor accountable will be easy, but history has shown that the U.S. federal government, with all of its agreements, power, and resources, still struggles to bring criminals to justice.

Our March 31 video discusses public comment on HHS's proposed rule. Watch it here.

But They Are Just In Canada!

The FDA warned 1,000+ Lexier's customers that his company had sold counterfeit Botox.

Was your doctor among them?

Yes, the U.S. and Canada have an extradition treaty, but an indictment by one country does not mean that the other country must immediately turn over that individual. People have rights, and while Lady Justice is known for being blind, she is not known for being swift. For example, a federal grand jury indicted two companies and five individuals on December 3, 2014 for illegally importing and distributing over $18 million worth of misbranded prescription drugs and devices to doctors across the country. While both of the companies and four of the five individuals had cut plea deals with the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) within about six months, there was one person who did everything he could to keep himself out of a U.S. courtroom: Tzvi Lexier, a citizen of Canada.

Even though he was a principal at both of the companies that had already pleaded guilty, Lexier used every legal tactic he could to delay. He questioned how a court in Virginia could have any rule over him. He fought the Canadian government to prevent his extradition. Forty-three months after the initial indictment, after all of his stalling tactics ran their courses, Lexier finally saw the inside of a U.S. courtroom on July 26, 2018. It took years of resources and dedication by the DOJ to finally get their man, but only a few months before that man pleaded guilty. In January 2019, Lexier received his prison sentence.

The outcome against Tzvi Lexier was a best-case scenario. The DOJ persevered, and the bad guy went to jail. However, there have been other cases where, despite all the best efforts, defendants dragged things out until there was no oxygen left in the room. Kris Thorkelson, also a Canadian citizen, was the CEO of CanadaDrugs.com. A U.S. district court indicted his company, several related companies and various individuals in November 2014, and Thorkelson did all that he could to slow-walk his case into a U.S. courtroom. The only time that Thorkelson showed up in court was in April 2018 to enter his guilty plea and to receive a five-year probation that included a six-month period of home confinement.

Even when U.S. law enforcement knows where a suspect is, they cannot always get them. In 2017, the DOJ indicted 28 people as part of Operation Denial, a major fentanyl pill and powder drug trafficking case that stretched across the Pacific Ocean from China to the U.S. and Canada. One of those individuals was Jason Joey Berry, a Canadian who helped run a fentanyl drug ring from prison while he was serving a sentence for manufacturing and selling counterfeit pills in Montreal. As of November 2019, the DOJ was seeking his extradition, but Berry is currently serving the remainder of his Canadian prison sentence. It is not clear when or whether the U.S. will be able to try him.

When There Is No Extradition Treaty Or Statute In Place

If the resolution against Tzvi Lexier is a best-case scenario, a worse-case scenario would be prosecuting a citizen of a country with which the U.S. does not have an extradition treaty or a country that does not consider counterfeiting prescription drugs a crime. There are 195 countries in the world, and the U.S. lacks extradition treaties with about 75 of them.

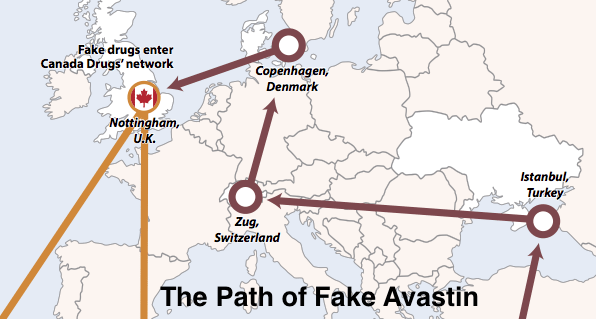

The People’s Republic of China, one of the global leaders in the production of legitimate pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients, has a history of producing counterfeit medicine and is one of the countries with which the U.S.has no extradition treaty. The DOJ indicted several Chinese nationals as part of Operation Denial, but it is unlikely they will be held accountable for the countless lives ruined or destroyed by the fentanyl they illegally shipped into the U.S.

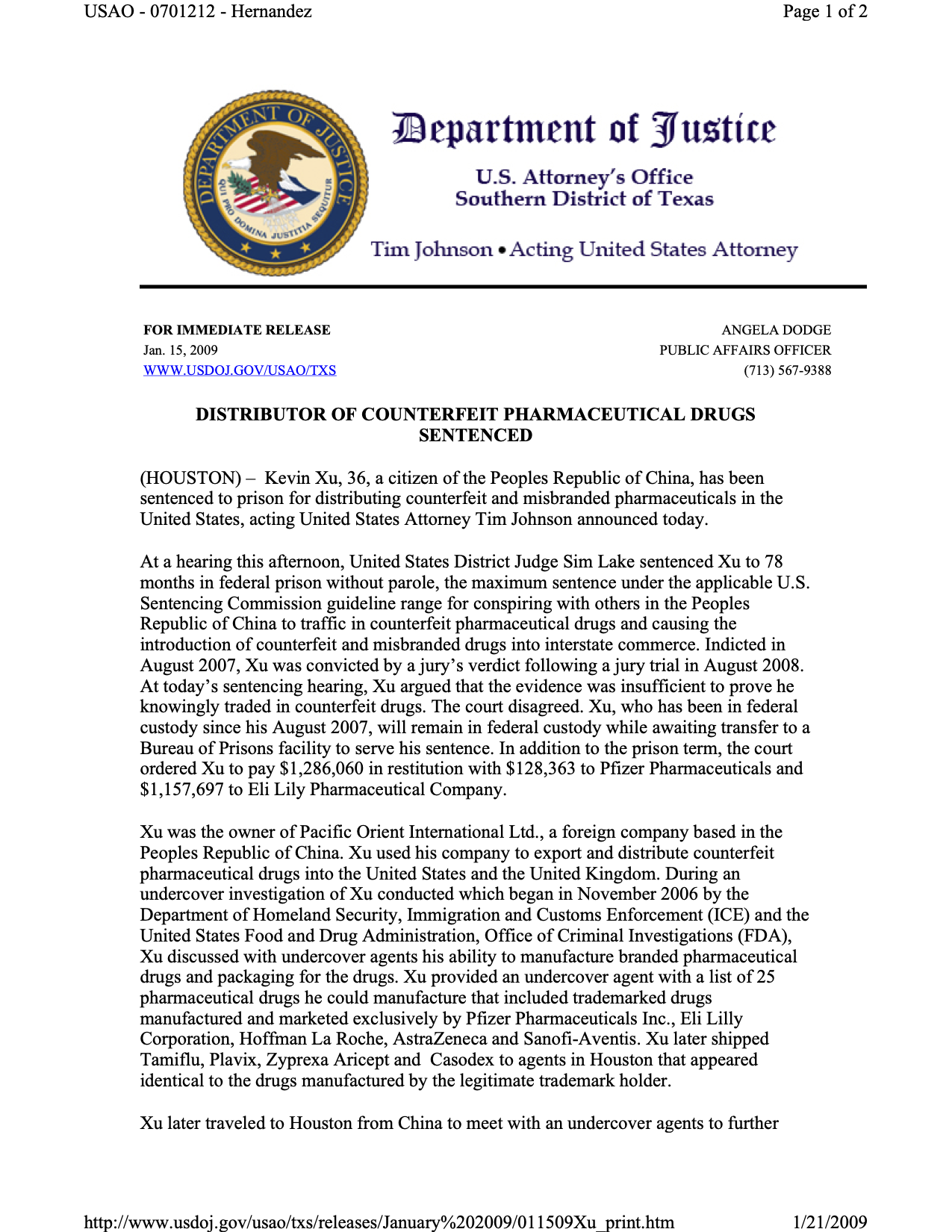

In cases like these, federal agents may trick a suspect into coming to the U.S. In August 2007, undercover federal agents scheduled a meeting with Kevin Xu, a citizen of the People’s Republic of China, to discuss a counterfeit prescription drug deal. During a previous meeting at the Bangkok Airport in Thailand in March 2007, Xu had provided a list of 25 brand-name drugs by different companies that he could counterfeit. Had Xu not come to that meeting in Texas, federal agents would never have been able to arrest him.

If the federal government, with decades of experience, legal agreements, and resources still has to fight for years to bring foreign drug counterfeiters to justice, it is difficult to understand how states think they can do as good as or better with less at their disposal.

Sources for this week's video and blog

- "View Rule: Importation of Prescription Drugs, ” Executive Office of the President, Spring 2020.

- “Second Protocol Amending Extradition Treaty with Canada,” 107th U.S. Congress (2001 - 2002).

- Indictment, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Virginia, December 3, 2014.

- “Canadian Companies Fined $45 Million and Ordered to Forfeit an Additional $30 Million for Smuggling Misbranded Pharmaceuticals into the United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, August 15, 2015.

- Jurisdictional Challenge, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Virginia, May 31, 2016.

- Tzvi Lexier v. Attorney General of Canada, Supreme Court of Canada.

- “Supreme Court of Canada Bulletin,” Lexology.com, July 6, 2018.

- “Medical Company Executive Sentenced for Smuggling $18 Million in Misbranded Pharmaceuticals into United States,” U.S. Department of Justice, January 18, 2019.

- “Four Additional Chinese Nationals and Six Additional U.S. Residents Indicted in North Dakota in International Drug and Money Laundering Conspiracy Involving Opioids,” U.S. Department of Justice, April 27, 2018.

- Indictment, U.S. District Court, District of North Dakota, Eastern District, September 21, 2017.

- “Two Inmates in Quebec Among Alleged Leaders of Opioid Ring,” The Globe and Mail, October 17, 2017

- “Extradition Law in the U.S.,” Wikipedia

- “Safeguarding Pharmaceutical Supply Chains in a Global Economy,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, October 30, 2019.

- Katie Lewis “China’s Counterfeit Medicine Trading Boom,” CMAJ, November 10, 2009.

- “Distributor of Counterfeit Pharmaceutical Drugs Sentenced,” U.S. Department of Justice, March 15, 2012.

- “The Mysterious Case of Kevin Xu,” Dan Rather Reports, aired September 14, 2010.