Alternative Funding Programs: Offshoring patients, importing risks

Many alternative funding programs are lowering employer costs by endangering American patients.

65% of U.S. workers get healthcare coverage through insurance self-funded by their employers, and employers are continually trying to keep those insurance costs in budget. Some employers pay third-party vendors offering “alternative funding programs” (AFPs) that promise to save their self-funded plan money through unscrupulous actions, like excluding coverage of higher-cost medicines that treat conditions like cancer, HIV, rheumatoid arthritis and diabetes.

They force employees to apply to Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs) to get medicine for free or to use illegal, foreign pharmacies that dispense non-FDA-approved medicine from entities that are not licensed by their state Board of Pharmacy.

Used an alternative funding program?

PSM is researching alternative funding programs and would like learn from patients and administrators who have encountered them.

Share this handout to explain the problems with alternative funding programs.

Forcing employees to use patient assistance programs can cause treatment delays for patients and it also raises ethical issues about exploiting PAP funds for profit. In 2023 AbbVie filed suit against vendors that allegedly fraudulently enrolled hundreds of ineligible patients into these programs.

The other technique, forcing employees to use unlicensed illegal foreign pharmacies, is also both illegal and unethical because it forces patients to take non-FDA-approved versions of medications to treat lifesaving conditions.

This practice carries civil and criminal liability for employers but not patients. You can confidentially report employers and vendors who use it to Homeland Security Investigations: Email iprcenter@hsi.dhs.gov, denoting “AFP” in the subject line. You can also report them to PSM by emailing editors@safemedicines.org.

Importing medicine from overseas pharmacies is illegal and dangerous

There isn’t much debate about personal importation being illegal (it is, and facilitating many people breaking the law is likely just as illegal), but we want to focus on the safety aspects.

Buying medicines directly from foreign pharmacies side steps the Drug Supply Chain Security Act tracking system (commonly called "track-and-trace"). This opens up a channel for bad actors to sell Americans fake or substandard drugs that may contain no medicine, the wrong amount of medicine, the wrong medicine, or dangerous contaminants. Patients buying outside the track-and-trace system either get the lookalike of an FDA-approved medicine that should not exist outside the U.S. (a fake), or a medication made for a foreign market. Medicines made for foreign markets don’t have the same level of FDA-scrutiny, even if they have the same name.

Counterfeit medicines are much more prevalent in foreign drug markets than they are in the U.S. Worse, American patients have no recourse if a foreign pharmacy sells them bad medicine. Foreign pharmacies don’t operate under U.S. law. U.S. regulators have no control over them, and prosecuting them is sometimes so difficult they go unpunished.

Can we explain the DSCSA in just 90 seconds? We did it for Congressional staff. Watch this video to get the 90 second DSCSA knowledge bomb.

Personal importation is illegal

Although alternative funding programs are pushing American patients into drug importation to get medicines they need, importing foreign medicines for personal use is still illegal in the United States. PSM was a party in a recent case that confirmed that personal importation is illegal in federal court. While the government doesn’t usually prosecute individuals for importing medicine, it does prosecute businesses for introducing unapproved and misbranded drugs into interstate commerce. Customs and Border Protection also confiscates illegally imported medicine at the border.

Patients getting their medicine by mail order is already a controversial topic in the U.S. because of concerns about temperature, handling and timeliness. It’s terrible and dangerous to force patients to rely on international mail and customs clearance for life saving prescription drugs—even more so when it’s only because employers are skimping on their employees’ health insurance programs.

Are drug counterfeiters around the world really fooling Americans with fake medicines for serious illnesses?

In March 2024, Indian police shut down a gang that sold counterfeit cancer medications to desperate patients. The gang, which included pharmacy and hospital employees collected old vials of Keytruda and Opdyta (sold as Opdivo in the U.S.) and refilled them with a common anti-fungal medicine. They distributed at least 7,000 of these vials and investigators say some their fake medicine they made its way into the United States.

An AFP vendor might push an American patient to accept a cancer medicine made for the India market because "it's the same" as the FDA-approved drug. The two products could only be considered the same if the FDA and Indian regulators were equally able to find and eliminate counterfeiters. There have been at least nine counterfeit drug busts in Delhi in the last year. Counterfeit medicine is a much worse problem in India than in the U.S., and it isn't safe to treat the products as equivalent.

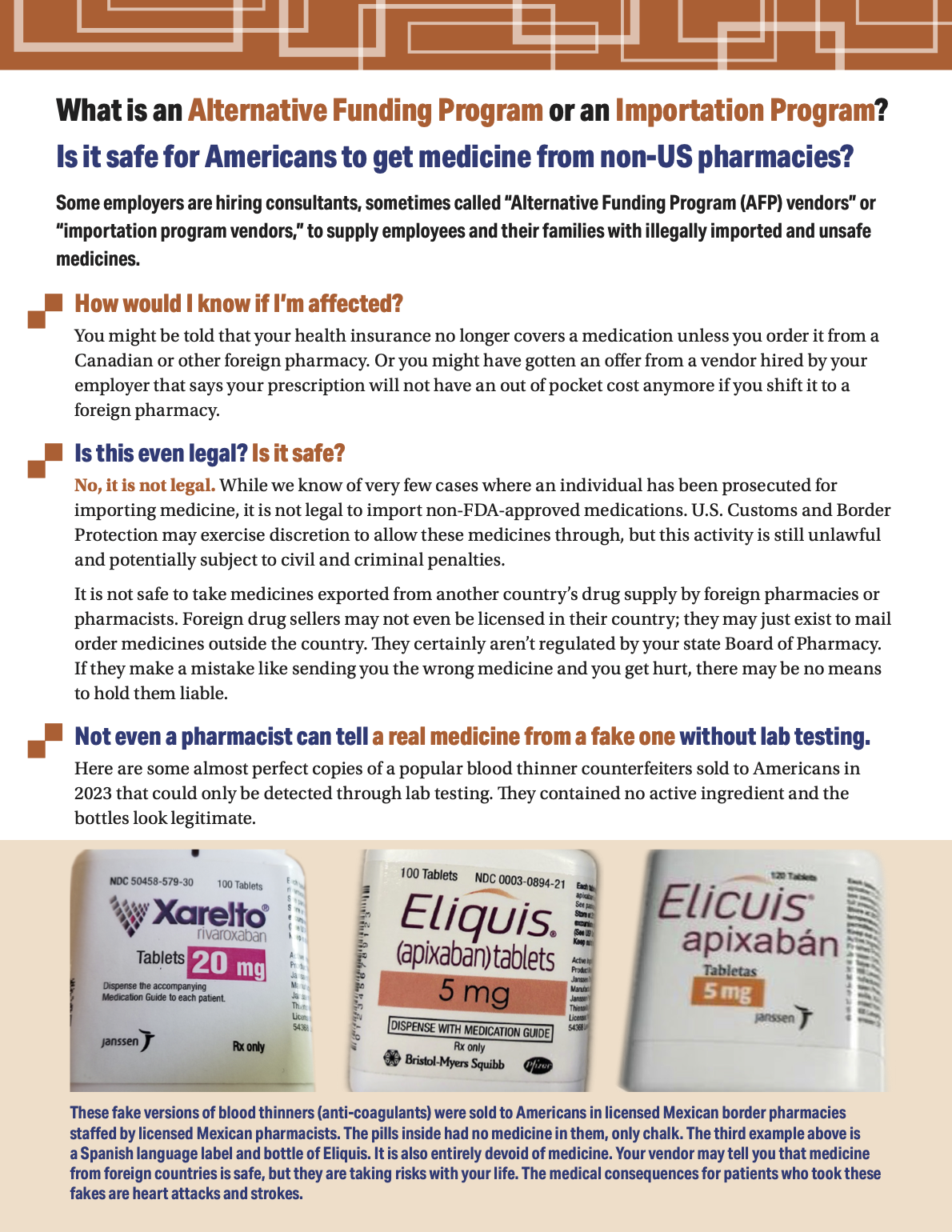

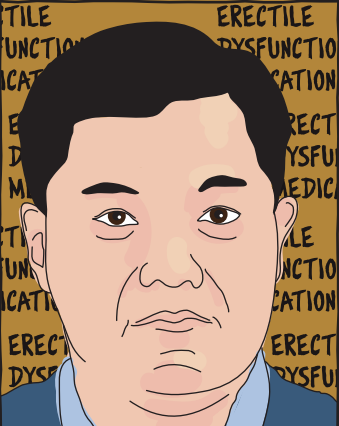

In 2020, PSM covered the problem of fake anticoagulants (blood thinners) being sold to Americans. These counterfeits had no active ingredient and were so picture perfect that even pharmacists would have had trouble identifying them as fake. These were clearly made to fool Americans, as they we were labeled and packaged in English instead of the native language of the country investigators found them in.

These cases demonstrate the real threat AFP-forced personal importation poses to Americans. According to their own information, some of the drugs AFP vendors are carving out of standard coverage include medicines for asthma, cancer, epilepsy, hepatitis, HIV, pulmonary hypertension and organ rejection. America's most vulnerable patient populations need these treatments, and regulators have reported counterfeits of both FDA-approved and foreign versions of them.

Because AFP vendors are working outside the U.S. track-and-trace system, there is no way to know whether employees forced into their programs are receiving legitimate FDA-approved medicines or what the vendor supplies as a “foreign equivalent.”

Have foreign counterfeiters been caught selling fake medicine to Americans before?

Unequivocally, yes. Criminals, both on- and offline, have sold fakes of lifesaving therapeutics to Americans. These are the same kinds of vendors that look pretty good when Americans go looking for "safe" pharmacies overseas.

Kevin Xu, a Chinese national, manufactured counterfeit medicines and sold them over the Internet to individual Americans and to wholesalers. His counterfeits included Casodex (for prostate cancer), Zyprexa (an anti-psychotic), Plavix (prevents blood clots), Aricept (treats Alzheimers) and more. He received a 78-month federal prison sentence for distributing counterfeit and misbranded pharmaceuticals in the United States in 2012.

One of the most well known incident of sales of fake medications to Americans involved CanadaDrugs.com, an online Canadian pharmacy with a wholesale business that sold non-FDA-approved medication to hundreds of American physicians. In 2018, CanadaDrugs pleaded guilty to selling misbranded and counterfeit medicines, including a fake versions of a drug called Avastin, which treats lung, liver, and kidney cancer.

Alternative funding programs deny Americans access to safe medicines

PSM is sensitive to the problem of rising healthcare costs, but it is fundamentally unjust and unsafe to cut those costs by hobbling the employer-provided health insurance coverage of Americans and then forcing them to beg for free meds or to illegally import medicine from unlicensed and unregulatable pharmacies.

Ultimately, employers are forcing vulnerable employees to take risks with their lives so that they don’t have to provide the health insurance they were promised when they were hired. When they conspire to violate federal law and bring illegal non-FDA-approved medicines into the country, they should face legal and financial consequences for this exploitative behavior.

Further reading on Alternative Funding Programs

A new wave of middlemen offers 'alternative funding' for specialty drugs. Patients bear the risks, FierceHealthcare.com, October 14, 2025

"When it comes to AFP operations, experts are perhaps most alarmed by the international importation of drugs. While not every AFP will do international sourcing itself, it might facilitate it for clients through a partner. Meds from overseas have not been vetted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the law prohibits their importation in most cases. In a 2023 cease-and-desist to a vendor offering import services, FDA called international sourcing "particularly concerning” because of the trust employees place in their insurance that may keep them from questioning the legitimacy of the drug. In its letter, FDA threatened legal action, but that has not stopped companies from advertising these services."

A primer on copay accumulators, copay maximizers, and alternative funding programs , Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, August 21, 2024.

"AFPs can add significant confusion, stress, and medication access delays. The AFP process begins with the patient receiving a denial of their medication with no clear path forward. They are told the only way to access this medication is by enrolling with a third-party advocate for assistance. To comply with the advocate’s process of enrolling in a patient assistance program, patients must agree to share their financial and private health information with this external group. Patients are often confused by this process as the details were not made clear when they originally enrolled in their health plan. This multistep process can take months, and patients may ultimately be forced to switch to an alternate medication entirely (if available) or forgo treatment owing to the complexity and burden of this process."

Abbvie's filing for an emergency injunction in civil case Abbvie Inc. v PayerMatrix LLC, August 21, 2024.

"The recently obtained evidence reveals that Payer Matrix is now marketing a new “alternative funding” option to its plan sponsor clients and specialty drug patients that involves Payer Matrix and its partner “RxFree4me” coordinating the illegal importation of purported AbbVie medicines and other pharmaceutical manufacturers’ medicines from outside the United States at reduced prices and falsely and misleadingly representing to the patients and their doctors that the medicines are government-approved versions of AbbVie medicines." This injunction request was denied in April 2025.

Read NASTAD's 2025 AFP brief for those serving HIV/AIDS patients