August 27, 2020 video: Behind the Scam: When Labels Lie

Did you miss our August 5th episode? Watch it here and read our accompanying blog.

On August 5th, we showed you how a classic counterfeiting technique, Uplabeling, works. This week's video discusses discusses a real-life example of “Uplabeling,” which is a technique that counterfeit criminals have used in the past to make major profits. Learn about what happened in 2002, when counterfeiters in Florida slipped diluted anemia medicine back into the legitimate drug supply.

Uplabeling in the real world

Timothy's father testifying, November 2005.

(Source: C-Span)

Learn more about the case.

In 2002, a 16-year-old liver transplant patient in Deer Park, New York, was prescribed 40,000 unit per milliliter Epogen to treat his postoperative anemia. His pharmacy filled his prescription and the label looked right, but the medicine he actually received was twenty times weaker than it should have been. For eight weeks, the teenager endured injections that left him screaming and doubled over in pain. His doctor was mystified. As law enforcement unraveled the scheme the FDA issued a counterfeit warning, and then the young man’s pharmacist called to explain.

How did diluted Epogen reach patients?

Katherine Eban's 2005 book offers an in-depth look at drug counterfeiting in this period.

A few months earlier, a small pharmacy in Miami bought 110,000 vials of low dose Epogen from a licensed and reputable wholesaler. But instead of dispensing the Epogen to patients, the pharmacy sold the vials to a counterfeiter named Jose Grillo.

Grillo transported the temperature-sensitive vials in paint cans to a trailer. After soaking the vials, counterfeiters rubbed off the low-dose labels and replaced them with new fake ones. Suddenly, the vials were a higher dose product.

Criminal wholesalers sold and resold the vials until the diluted Epogen landed at a small wholesaler in Arizona that sold them back to the original wholesaler in Florida. Each of the low dose vials originally sold for $25, but, after they were up-labeled, they were worth $470 each, making this scheme worth about $46 million.

The original wholesaler thought the vials were genuine, and placed them with the rest of the high dose Epogen stock. A national pharmacy chain bought them, and that is how a 16-year-old transplant patient in Deer Park, New York ended up with them.

Reform: Florida’s Seventeenth Grand Jury

After the Epogen case, the state of Florida convened a statewide grand jury to examine the practices of pharmaceutical wholesalers. In March 2003, a 47-page report detailed the scope of the problem within the state and made recommendations to improve safety. The report noted that an “alarming percentage of prescription drugs flowing through the wholesale market have been illegally acquired” through theft, patient drug buy-back rings, and illegal importation and that medicine sold by the over 1,300 wholesalers licensed in was “likely to become tainted due to improper handling or storage.” The grand jury could not determine how much of Florida's drug supply was stolen, mishandled, tainted, or uplabeled, but it concluded that any amount of adulterated pharmaceuticals was too much.

Florida’s Bureau of Statewide Pharmacy Services (BSPS) and Department of Health (DOH) were already improving drug security by cracking down on the enforcement of paper pedigrees that recorded who had manufactured and handled prescription medications when the grand jury was convened. The grand jury, however added recommendations, including strengthening permitting requirements and direct agency oversight of wholesalers; hiking penalties for pharmaceutical crime so that they were substantial felonies; allowing relevant state agencies to immediately seize and destroy offending pharmaceuticals or close establishments warehousing drugs in an unsafe manner; and requiring wholesalers to consistently use and verify pedigree records.

A 2012 analysis of Florida's pharmaceutical distribution regulations shows that the bulk of these recommendations were implemented.

When Bad Medicine Reaches Patients: Consequences for Pharmacies

Every pharmacist’s worst nightmare is giving a patient medicine that harms them. The unfortunate flipside to that patient harm coin is that a pharmacy can be sued for dispensing a counterfeit prescription drug to a patient. In Fagan v. AmerisourceBergen Co., 356 F.Supp.2d 198 (E.D.N.Y. 2004), the 16-year-old victim of the counterfeit Epogen sued the wholesaler and the pharmacy that dispensed the medicine to him. Part of the court’s ruling was that a pharmacy MIGHT be liable for counterfeit medicines if the two following conditions, among others, are met:

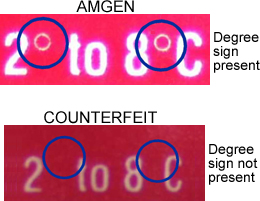

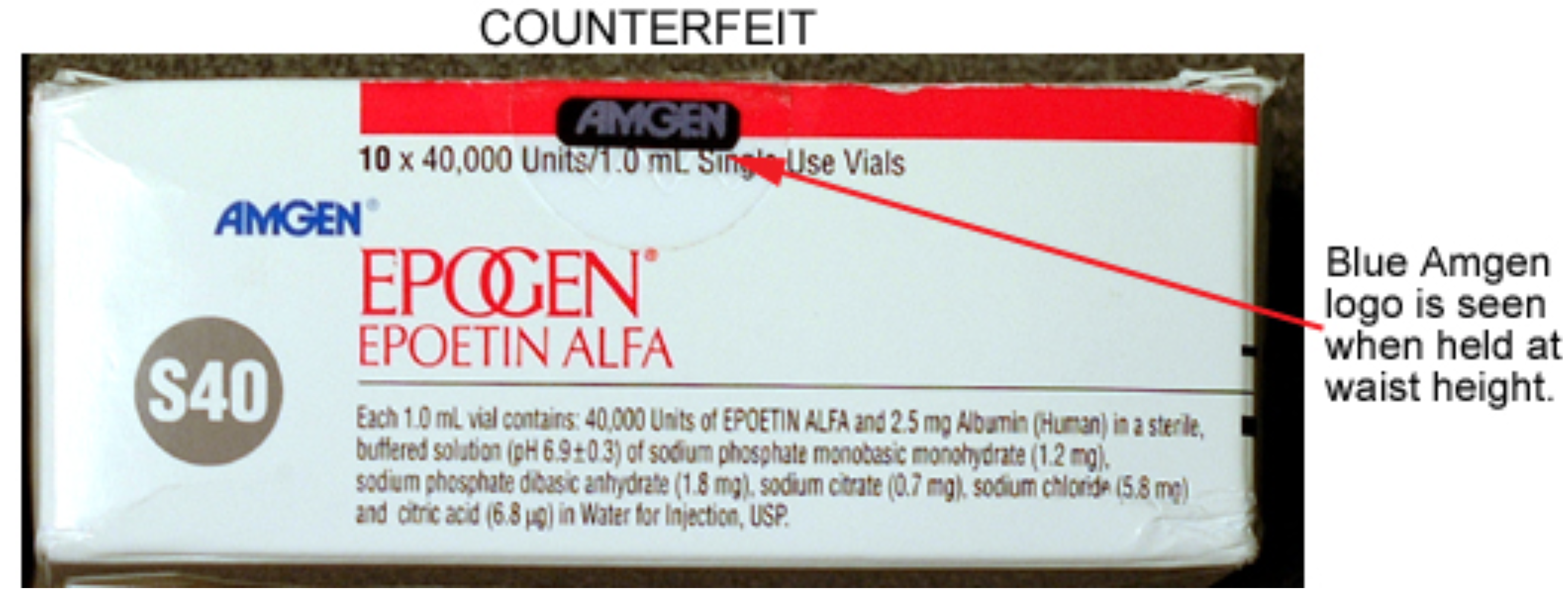

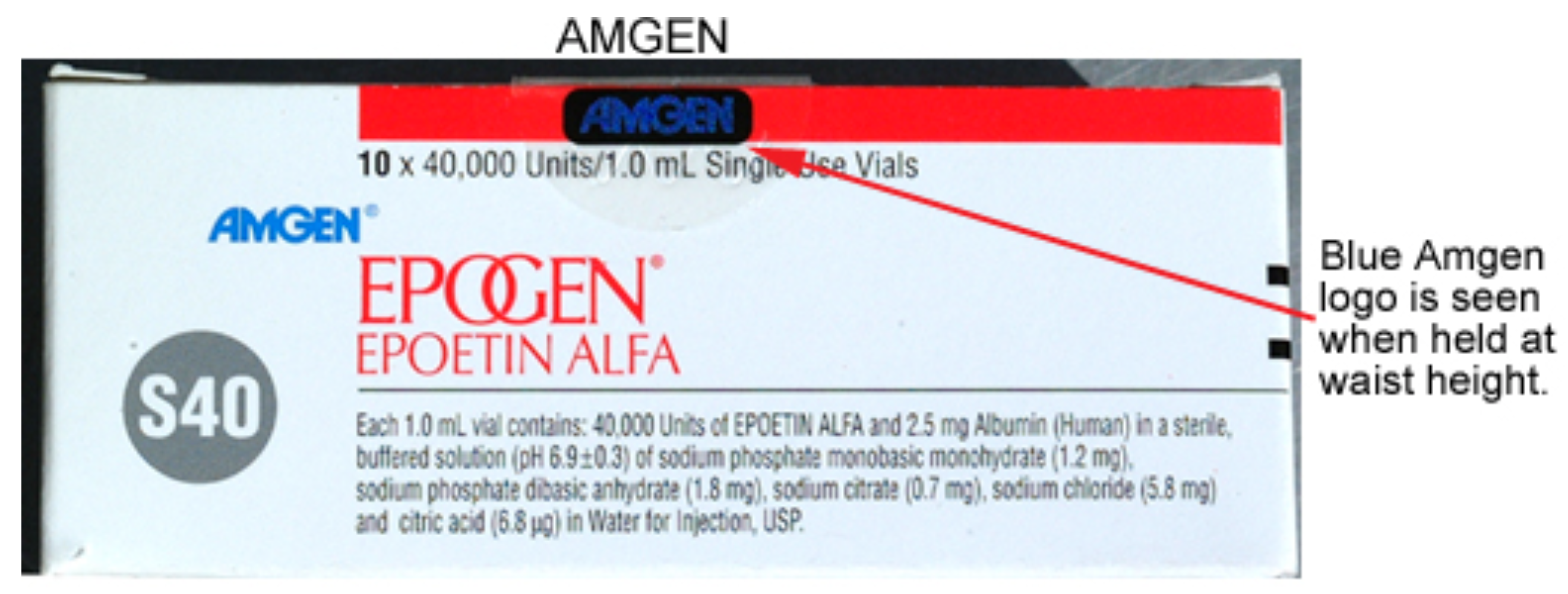

- There is a defect on the face of the counterfeit drug’s label, which means that the defect could have been discovered through reasonable inspection of that label, and

- A pharmacist failed to discover the defect.

In this case, both of these conditions were met. Ultimately, this particular case settled out of court, but it shows that there is a potential path for a plaintiff to hold a pharmacy liable for harm caused by providing the patient with a counterfeit medicine—whether the drug comes from what purports to be a licensed wholesaler or is from a foreign pharmacy online.

Real and counterfeit Epogen packaging that was circulating in 2002.

Federal Reform: A National Track-and-Trace System

With advances in technology, examining physical papers and making phone calls to ensure prescription drugs are quickly becoming a thing of the past. In 2013, Congress passed the Drug Supply Chain Security Act which mapped out a 10-year plan to build systems to identify and trace prescription drugs as they are distributed in the United States and establish national licensing standards for wholesale distributors and third-party logistics providers. Close to being fully implemented, the U.S.’s track-and-trace system allows for the electronic tracking of a prescription drug’s entire life from the manufacturing floor all the way to the moment it is dispensed to a patient. No other country in the world has a system like it, and it is the best way to keep counterfeit and substandard medicine from reaching American patients.

Any drugs purchased from outside the U.S.’s secure drug supply—whether they come from an individual purchasing medicine online from a foreign pharmacy or from a state importing drugs from a foreign country—cannot be incorporated into the track-and-trace system. The dangerous shortcomings of Florida’s wholesale market in the early 2000s illustrate how illegitimate drugs can easily cross borders and make their way to patients in other states, posing a threat to the health of all Americans.

Sources for this week's video and blog

- “Drug Importation, Counterfeit Medications And The Pharmacist’s Liability: A Case Study And Legal Precedent,” The Partnership for Safe Medicines, July 18, 2018.

- “Report: Prescription Fraud Penalties Needed,” Herald-Tribune, March 6, 2003

- First Interim Report of the Seventeenth Statewide Grand Jury, Supreme Court of the State of Florida, Case No: SC02-2645, February 2003.

- Nathan Adams IV, Shannon Britton Hartsfield, "Drug Wholesaling In Florida—The Top Five Myths," JD Supra, September 7, 2012.

- “If The Illegally Imported Medicine Does You Harm, The Criminals May Never Be Punished,” The Partnership for Safe Medicines, May 2018.

- “Miami Man Gets 12 Years in Prison for Prescription Drug Scheme,” InsuranceNewsNet, May 20, 2008.

- “Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA),” U.S. Food and Drug Administration, updated May 8, 2020.