The End of GLP-1 Compounding

A version of this post appeared in our executive director Shabbir Safdar's LinkedIn on May 22, 2025

On May 22nd, federally-registered compounding facilities will stop making tirzepatide in response to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s end of shortage determination. This transition is significant for patients, and we at PSM think there are four things you should be watching for.

A safer drug supply

The FDA was pretty clear in their December 19, 2024 letter when they wrote:

Although compounded drug products can provide treatment options for patients during a drug shortage, compounded drugs have not undergone FDA premarket review for safety, effectiveness, and quality, and lack a premarket inspection and finding of manufacturing quality that is part of the drug approval process.

Further, drug products that meet the conditions under section 503A are not subject to CGMP requirements and are subject to less robust production standards that provide less assurance of quality. Accordingly, the statute includes restrictions on compounding drugs that are essentially copies of commercially available drugs and approved drug products that are not on FDA’s drug shortage list.

These restrictions help reduce the risk that compounders will prepare these unapproved drug products for patients whose medical needs could be met by an approved product. This helps to protect patients from unnecessary exposure to drugs that have not been shown to be safe and effective, and that offer fewer assurances of manufacturing quality.

Compounded drugs have not undergone FDA premarket review for safety, effectiveness, and quality, and lack a premarket inspection.

Compounded medicine is an important safety valve for shortages, but the FDA does not guarantee it is safe or effective and facilities that make compounded medicines, such as 503B outsourcing facilities, don’t have to be inspected by the FDA before shipping products. In contrast, branded and generic medicines are rigorously tested to gain FDA approval and facilities that manufacture FDA-approved products are inspected before they start production as well as other times during the approval process. That’s why generic and branded medicines are FDA-approved, and compounded products are not.

There are also strict labeling requirements for branded and generic products, whereas the requirements for compounded ones are much more lax. This has led to many dosing errors by patients using compounded medications.

Compounded medicines don’t have the same serialization (DSCSA) as generic/branded medicines, which means that they are more difficult to track and recall if they harm patients.

The list goes on and on. Every compounded GLP-1 that is replaced by a generic/branded product is a win for safety.

Impediments to GLP-1 access because of insurance and pharmacy benefit manager greed

There are definitely U.S. patients who do not have access to GLP-1s, often because an insurance company, employer, or pharmacy benefit manager doesn’t want to cover them.

It’s always in vogue to talk about drug manufacturers being the driver of cost barriers, but this is not an honest assessment. For years, legislators have claimed that manufacturers set insulin prices, but in 2024 the Federal Trade Commission investigation revealed that pharmacy benefit managers had driven prices of insulin up and pocketed the price increases.

Between 1999 and 2017 the list price of Humalog soared to more than $274—a staggering increase of over 1,200%. While PBM respondents collected billions in rebates and associated fees according to the complaint, by 2019 one out of every four insulin patients was unable to afford their medication.

Denial of coverage for GLP-1s, either in structure, as with Medicare, or by plan sponsors, should not be solved by providing patients a less safe alternative. It should be solved by pressuring insurance plans to provide the coverage they owe their covered lives.

Drug manufacturers have built a supply chain for patients that routes around the trillion dollar PBM / insurer market. I feel that’s a pretty good faith effort to make it as affordable as possible.

Telehealth providers exploiting “patient need”

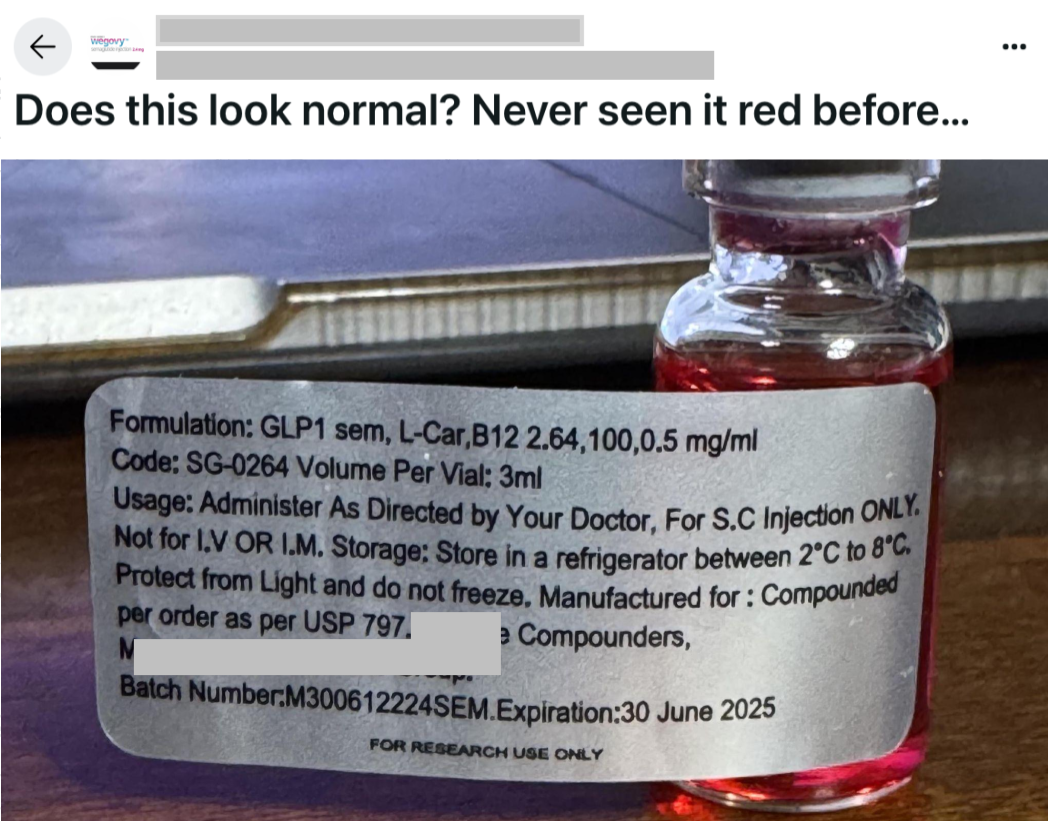

We are particularly concerned about unscrupulous telehealth providers changing doses and mixing additives into compounded versions of GLP-1s in order to allow them to continue selling compounded products. Internet discussion groups are full of stories of patients learning, for the first time, that their telehealth provider and their captive prescriber have decided they suddenly need GLP-1s compounded with vitamin B, or that they need a specific dose not offered commercially.

These patients are surprised because the change had nothing to do with them or their needs. It was driven by a telehealth provider and a likely captive prescriber.

When telehealth providers drive these changes, it is not some sort of loophole; this is just fraud. Since none of these new formulations or doses have been through safety trials, providers are effectively performing a massive unsanctioned human trial that is deeply unethical, and illegal, to boot.

A flood of criminal activity

The tremendous demand for GLP-1s has generated so much crime and patient danger that it makes my head spin. We’ve seen an insane amount of illegal compounding, marketing, manufacturing, prescribing, and administration. Virtually every contemporary drug-related crime I’ve seen in the pharmaceutical space has been tried in the GLP-1 space over the last five years.

Patients struggling with access will be seeking new ways to access GLP-1 medication, and consequently will be exposed to fraud at levels we haven’t seen since the onset of the COVID epidemic.

What should be done?

Crime flourishes where access struggles. The sooner we force insurance companies and PBMs to provide coverage for these medicines for those that qualify, the smaller a target criminals will have.