Why are price cap proposals on medicines dangerous to pharmacies and patients?

Price cap proposals, like upper payment limits currently being debated by prescription drug affordability boards (PDABs) and Medicare maximum fair prices (MFPs), often assume a simple drug/price supply chain which doesn’t reflect reality in the United States. They also don’t account for the fact that members of the drug/price supply chain will react to price caps in ways that could bankrupt pharmacies and reduce patient access.

Colorado approved an upper payment limit on Enbrel a few days after we posted this. We anticipate that this decision will be bad for pharmacies and patients.

The U.S. healthcare system is uniquely complex.

Pharmaceuticals in the United States have an incredibly complex supply chain. Everyone agrees that more should be done to address the cost of medicine, but developing workable cost-reduction policies is challenging. This is because unlike a hardware store, where the maker, distributor, and retailer of a hammer are linear and all actors fear competition, the U.S. healthcare market is far more complex.

Healthcare system players like pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) gatekeep patients from their local pharmacies. It’s as if the maker or distributor of a hammer could tell your local hardware store whether customers could use your hardware store and what you were allowed to charge for the hammer, regardless of how much it costs for you to buy it.

A teachable moment

Recently Dr. Emily Zadvorny of the Colorado Pharmacists Society provided public comment to the Colorado Prescription Drug Affordability Board about their efforts to set upper payment limits for several medicines. Several other states are in this process, and the federal government has been engaged in setting MFPs for medicines in Medicare.

Dr. Zadvorny’s testimony underscored problems with price-setting policy solutions to healthcare costs in the U.S.

up to 90% of independent pharmacies are already saying they will not participate in the medication in the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, precisely because there is no guarantee that they can not be underwater on those drugs. [Dr. Emily Zadvorny, 7/11/2025]

Dr. Zadvorny was talking about multiple risks to pharmacies and to patients, which we’ll explain below.

PBM reactions to price caps that affect pharmacy

Most price cap proposals only concern themselves with the maximum price manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies, and insurance companies can charge or reimburse for a medicine. Reducing the maximum price means that players, such as PBMs, will make less money when drugs are dispensed to patients.

Policies like UPLs and MFPs don’t always prevent monopolistic players like PBMs from lowering reimbursements to maintain their profits under the price cap. For example, imagine a medicine that costs a pharmacy $1,000 to purchase. The PBM makes $150 on that medicine and reimburses the pharmacy $1,010. If a price cap says that you can only charge $500 for the medicine, the PBM is likely to lower the reimbursement for the pharmacy to $350. The PBM maintains their $150 profit, and the pharmacy loses money.

Even if the UPL rules say that a medicine can only be sold for $500 and must be reimbursed at the same price of $500, the pharmacy will make $0. Your local hardware store cannot stay in business buying and selling items for $0 profit, and neither can your local pharmacy. How will it pay for salaries, rent, insurance, utilities, and other costs of doing business?

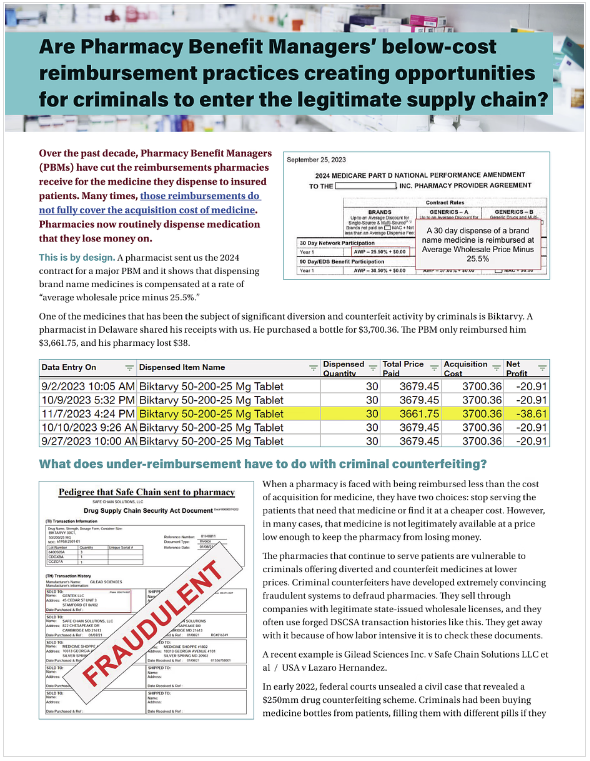

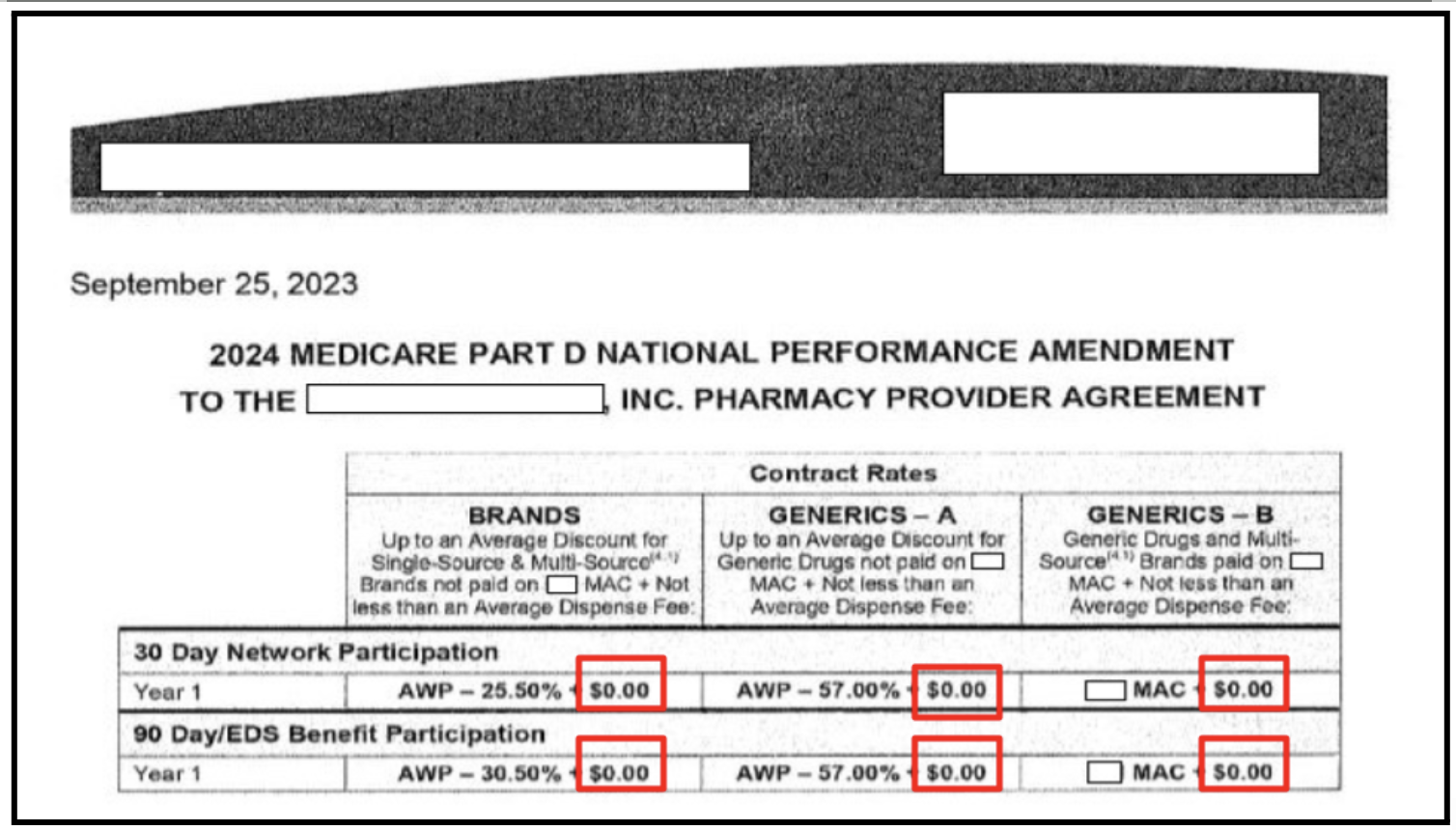

This 2-page summary explains the problem of PBM under reimbursements.

Pharmacies as financial lenders to the healthcare system

The Medicare MFP system sets a maximum reimbursement Medicare will pay for a medicine, but leaves the cost of medicines untouched. It requires drug manufacturers to rebate pharmacies for the difference between the two. If the manufacturer is not required to compensate the pharmacy for their full cost, it will be catastrophic. Pharmacies can not stay in business without being made whole on their costs or without making profits.

However, there is another problem: The time between when pharmacies purchase medicine and when they are fully reimbursed is an enormous interest-free loan that pharmacies, which are already operating on razor thin margins, cannot afford. Estimates are that this could be thirty days, or even more. In January 2025, 3Axis Advisors found that under Medicare’s drug price negotiation program pharmacies could see a weekly cash flow shortfall of $10,838.25 compared to prior operations. Nearly 2,300 pharmacies shut their doors during 2024, primarily for financial viability reasons, and cash flow problems because of these proposals will accelerate closures.

Read Unpacking the Financial Impacts of Medicare Drug Price Negotiation on the 3Axis site.

What effect will this have on patients?

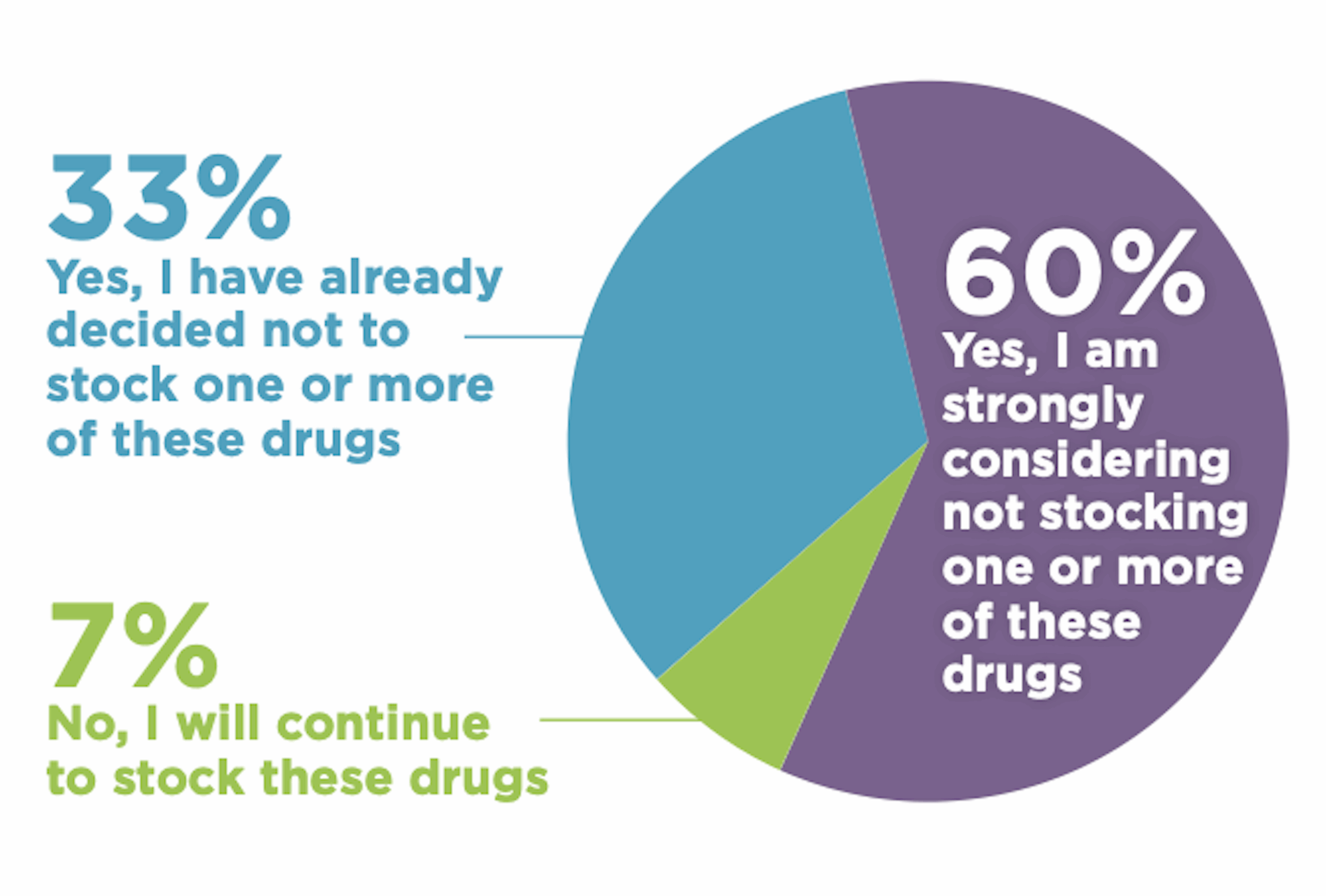

Community pharmacies are wary of stocking price controlled drugs from the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program (NCPA member survey, January 2025)

Many pharmacies have already decided not to stock price-controlled medications rather than risk financial ruin. In fact, the National Community Pharmacists Association (NCPA) January 2025 survey of independent pharmacies found that over 90 percent of independent pharmacies may decide, or have already decided, not to stock price controlled drugs from the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program.

Patients cannot get quality healthcare from a pharmacy that’s out of business or that can’t afford to stock the medicine that patients need. Additionally, PBMs may make less profitable price-controlled medicines harder to obtain by placing them on a harder to reach tier, or by hiking patient co-pays, which also impedes access.

Don’t pharmacies make their money on “dispensing fees” anyway, instead of the cost of medicine itself?

Dr. Zadvorny brought this up in her public comment:

We did get [a dispensing fee] into the rules. We got it into the law. But what I heard earlier today that concerns me is that it would be left up to private contracts to ensure that. I can tell you right now that a lot of private contracts are either pennies for a dispensing fee, or sometimes it's not even made whole.

It can be $0. I think if there's any possibility to pay for this, for the board to ensure that there's a fair dispensing fee, I would absolutely implore you to do that. The state of Colorado does gather, cost of dispensing surveys. And there is data on what the real cost of dispensing a medication is. I would encourage that the dispensing fee that's included in these UPL [upper payment limit] drugs is no less than what is in that data from the cost of dispensing survey. [Dr. Emily Zadvorny, 7/11/2025]

Dr. Zadvorny is referring to PBMs giving pharmacies a dispensing fee of a penny (yes, an actual penny) or a few cents for the cost of all the work that goes into dispensing a medicine. This, combined with reimbursements for the cost, or sometimes less than the cost of medicine, explains why pharmacies are wary of proposals that might incentivize PBMs to cut their reimbursements further.

The actual cost of dispensing has been studied in Colorado and at the national level. The state of Colorado does an annual survey of dispensing fees to ensure that fees paid to pharmacies for serving Colorado Medicaid members are aligned with the actual costs of dispensing. In 2025, that cost was estimated at $9.31 to $13.40 per prescription for non-rural pharmacies, based on volume.

A 2020 NCPA study determined a normal dispensing fee should be $12.40, with a higher fee of $73.58 for specialty medicines. Many of the medicines the Colorado PDAB are looking at for upper payment limits are considered specialty medicines.

Why can’t we have negotiated prices like Canada?

The Canadian healthcare system for medicine has shortcomings around patient access that we don’t talk about. However, one advantage they do have is a lack of pharmacy benefit managers. PBMs exist in Canada, but do not dictate the terms of every other player in the system as they do in the U.S. healthcare system.

What should we be doing instead?

Stakeholders from all across the supply chain are nearly unanimous in their calls for PBM reform. The business practices of PBMs hamper patient access and bankrupt pharmacies that provide critical patient care.

Managed Medicaid reform

States looking for savings ideas could learn a great deal from states that have reformed the role of PBMs in their Medicaid programs. West Virginia and North Dakota carved prescription drug benefits out of their managed program and saved $54 million and $17 million respectively in a single year. Kentucky moved to a single PBM in 2020 and documented $282.7 million in savings for the 2021-2022 cycle. For more information on savings in this area, see this NCPA publication “Medicaid Managed Care Reform.”

PBM reform to reduce costs in the private insurance market

- Markups at PBM-affiliated mail-order pharmacies were more than three times higher than those at retail pharmacies.

- Plan sponsor (employer) costs increased by 30 percent, while commercial pharmacy reimbursement decreased by 3% between 2020-2023.

- PBMs charged employers vastly different amounts for the same prescription medications.

- PBMs drove an increase in employer health care costs over the past four years.

For more information on prescription drug affordability boards and upper payment limits, see PSM’s website or the National Alliance of State Pharmacy Associations’s Prescription Drug Affordability Boards: Potential Risks to Pharmacy Reimbursement.